Chapter 2: The Center of the Herd

To recap Chapter 1: our earliest training on how to handle stress came from childhood.

If the people around us growing up didn’t show us how to process anxiety, grief, anger, or physical tension, we missed out on a core life skill. That made it more likely we’d leave the military with a backlog of unprocessed stress.

The bigger the backlog, the heavier it feels. Over time, we may end up chronically fatigued, agitated, or depressed from carrying that invisible weight.

When I came back stateside from Iraq, I felt like life couldn’t reach me anymore. It was like there was a six-foot wall of glass between me and everything else. Even my laughter had a hollow echo, it sounded forced. There were many moments like that, where I knew I was expected to express something, so I did, but inside I felt disconnected.

I lived like a ghost for years, eating without tasting, touching without feeling. That didn’t start to change until I learned that dealing with military stress often requires community.

I learned how deeply wired we are to be community animals. That infants can die if they go too long without touch. How even as adults, our nervous systems sometimes need others to calm down and feel regulated.

This is called “co-regulation.” It means trusting someone else enough to share the weight.

In April 2019, I went to a Veterans “coming home” workshop led by Dr. Ed Tick, author of War and the Soul. At that retreat, he shared a story that permanently changed how I deal with stress.

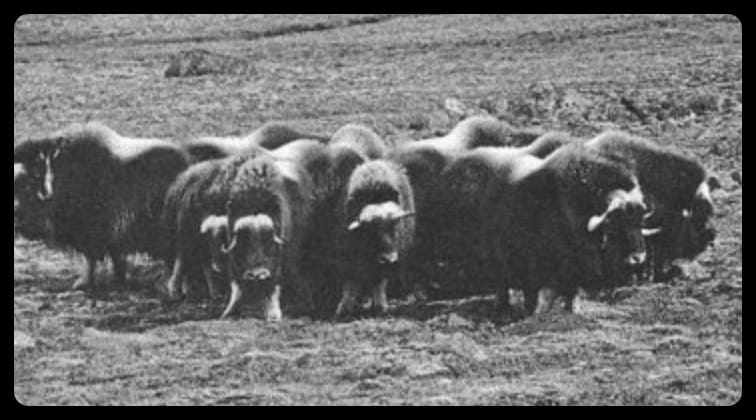

The story was about the Great Plains bison herds (often called the American buffalo), and how they live out a kind of relationship that could exist between warriors and society.

When the herd senses danger, the strongest bison form a protective ring around the most vulnerable: the calves, elders, sick, and most of the females. The bulls stand guard on the outer edge.

Hearing this, I remembered how I felt when Sept. 11th happened. I was young and strong. The right thing to do was clear. The city I was born in was attacked. It needed to be defended from further violence. The strong in the herd protect the weak. That’s the natural order of things. That made sense to me.

What I didn’t understand then was the rest of the story.

Dr. Tick explained that once the threat is over, something different happens to the bison in the outer ring—the ones who did the protecting. If any of them are distressed or injured, the herd moves them to the center.

Then, the rest of the herd surrounds them and cares for them until they recover.

This is the critical step I skipped.

I thought I was “OK” because I wasn’t physically wounded. I figured the resources and attention should go to those with visible, “real” injuries. I didn’t understand that emotional and moral wounds needed just as much care.

The problem was, at some point in the military, I decided it was better to be numb than scared. I didn’t realize you can’t shut off just one emotion. Going numb to fear means going numb to everything. Maybe you made a similar decision, and closed yourself off from certain feelings.

The guys in my platoon were in the same boat. We were expected to tighten up and “keep it together.” No one wanted to hear any griping about feelings. Then, when we left the service, we were supposed to re-enter society like we hadn’t brought home any pain with us.

When I came home, I avoided anyone and anything that reminded me of what I was carrying. I didn’t talk about my experiences because I didn’t want to weigh down the people I loved.

I didn’t want them to hear the harsh stories I carried and be tainted by what I’d experienced. Seeing them free of the pain I felt, and able to enjoy a carefree life, was one of the few joys left to me.

I purposely closed myself off from people. I was trying to protect them from realities I saw that didn’t match up with their image of America.

Or of me. I was also protecting myself. I was confused about what happened in Iraq, and questioned what I did there. I didn’t want to see disappointment in their eyes and be cut off from the herd. What if they judged me for how my service changed me?

How would people respond if I told them how my military service impacted me?

Letting that question hold me back—and not letting others share the weight—is the biggest “What if I had chosen differently?” I carry.

On one hand, I didn't give the people back home the chance to serve in their role. I kept the herd from doing what it’s meant to do: encircle the wounded and carry the load together. Even someone sick, young, or elderly could hold at least one rock from my rucksack. I thought I always had to be the strong one, carrying the whole pack myself.

On the other hand, looking back, the strength it took to carry all that pain is worth honoring. I don’t see it as a mistake, because I’m not sure anyone around me back then could’ve held those stories with care. I had emotional “bullets” stuck in me I didn’t know how to remove. I lashed out at anyone who tried. Bringing me to the center without the right people to support things could’ve caused more harm. As my friend and fellow Veteran Donny Reed put it, “We were dangerous animals in pain."

Still, I’ve come to see that there was another possibility.

I understand now that in healthy societies, warriors are welcomed home differently. When that Welcome Home is done well, everyone we love benefits from us being brought to the center. We get listened to until the words run dry. Seen. Honored. Held. And loved.

It’s a cycle of mutual care that helps everyone feel safer and more connected. It’s the kind of exchange that helps make up for the close bonds we left behind in military life.

It's a staggering loss to miss out on this.

For everyone.

I honor each of you reading this who has carried stories, and I recognize the strength that took. That strength will be needed again—when we find a community mature enough to help us pull out those bullets and handle the pain that pours out with them.

It wasn’t until 2023 (19 years later!) that I found the right people and began to share my full story.

I started noticing what numbed me: drinking, smoking, staring at screens. Instead of leaning on those things, I began unpacking the rocks I’d carried (the experiences that left a heavy impact) and sharing them.

I shared them carefully, one at a time, with people I trusted: friends, family, other Veterans. I learned to bring those stories out into nature, letting the wild places help carry their weight. Slowly, I felt alive again.

Self-reliance only took me so far. It wasn’t enough. Community took me the rest of the way.

Yes, our survival needs must be met first: food, water, shelter, and the confidence those things will be there tomorrow. That’s the foundation. Until those needs are met, our brain will struggle to focus on anything else.**

Once we have that foundation, it’s crucial to have a community that brings us to the center, listens to our stories, and helps share the weight we’ve been carrying.

It may be that PTS(D) exists because we haven’t evolved to live as individuals, disconnected from close, supportive community.

The culture of the military is group-based, but the “help” we often find when we return home isolates us and treats us as individuals. Many organizations don’t understand that some of our stress came from within close-knit groups—and needs to be healed in the same kind of close group connection.

I see it all around me: Veterans with invisible wounds ending up as misunderstood outcasts. I lived that life.

In the natural world, the wounded protectors at the edge of the herd aren’t left behind. They’re brought to the center. That’s the life I’m choosing now.

When we find our herd, we can stop carrying the weight alone.

So, how do we find the people who truly care?

Where do we go to be brought to the center and honored?

That’s the path ahead. Join me in Chapter 3: Our Stories Create Community.

*War and The Soul is still the best book I've read on what it means to return from war carrying invisible wounds.

** - If you or another Veteran you know needs immediate food or housing help call the VA’s National Call Center for Homeless Veterans hotline: (877) 424-3838. It’s staffed 24/7. Or contact your closest American Legion office if you don’t want to work with the VA.